Regardless of employment status, the customer will expect to receive a certain level of service, a cheery smile and a courteous response to their enquiry. Why then do organisations put a very different emphasis on engagement and motivation practices when it comes to their employed and nonemployed workers?

It would be ludicrous (and illegal in most jurisdictions) to suggest we should discriminate against female workers by only incentivising the males, or maybe having a bonus scheme for younger workers and nothing for those aged over 50. Yet organisations are more than happy to discriminate against non-employed workers by putting most of their motivational efforts into their employed workforce.

Earlier this year, Staffing Industry Analysts conducted an extensive global survey in partnership with ERE Media, which elicited full responses from 339 company executives from a wide range of industry sectors and 289 suppliers of HR/recruitment related products and services. We wanted to understand how organisations dealt with their non-employed workforce; how visible it was, how much effort they put into engaging and motivating it, and how joined-up and proactive the management of the ‘Total Talent’ that did work on their behalf was. The resulting report, ‘Total Talent Management: Towards an Integrated Strategy for the Employed and Non-Employed Workforce,’ was published in May.

The survey revealed a number of surprises in addition to motivational inconsistencies.

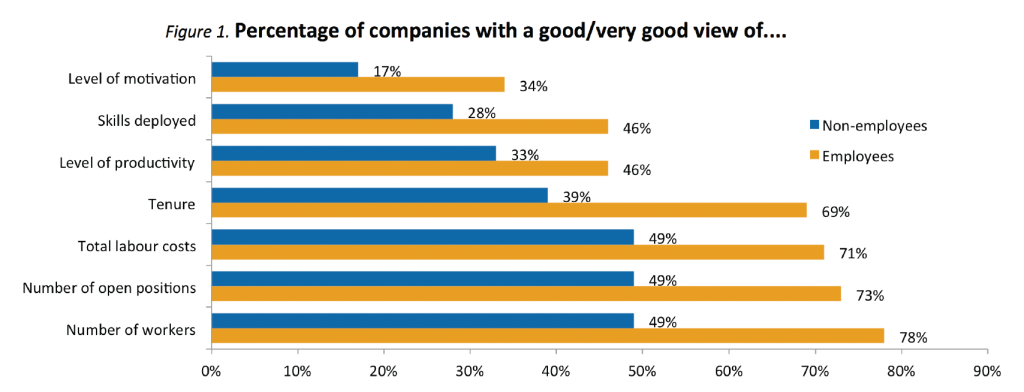

Lack of visibility is clearly a big issue. Organisations have a much better view of their employed workforce than the non-employed part (See Figure 1). Almost half of our survey respondents thought they had a good or very good view of the number of non-employed workers, the number of open positions they had and the total labour costs, but visibility was much worse when it came to issues relating to tenure, productivity, skills and motivation.

Understanding which worker-type is the best option in any particular circumstance is a mystery in most organisations and sourcing decisions are mostly being made in a vacuum.

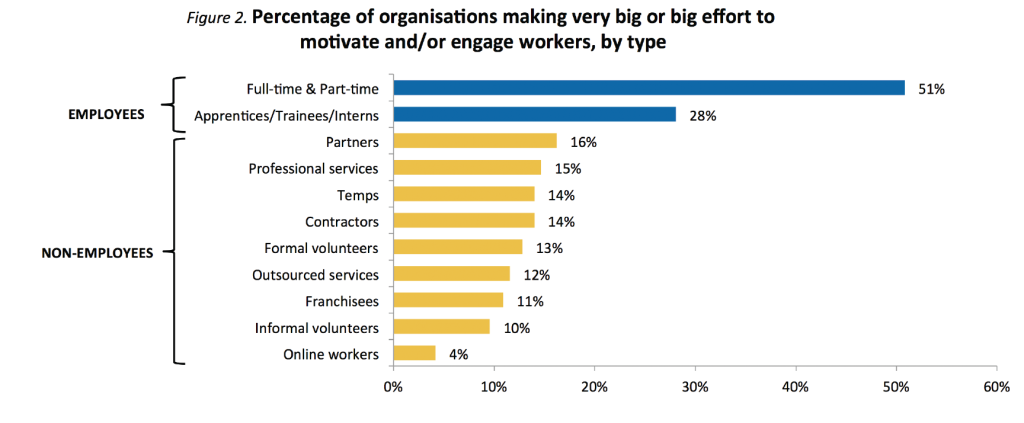

When we asked how much effort they put into motivating and/or engaging workers, there was a clear bias in favour of employed workers (see Figure 2). While it may seem obvious that an organisation might favour longer-tenured employees over those who are engaged for only days, weeks or months, many non-employed workers are on long-term contracts so the extent of the bias does appear rather overdone. In reality, many non-employed workers will be contributing to the organisation for longer periods than those with ‘secure’ employment contracts.

There are many different categories of non-employed workers. Those in contingent roles such as temporary workers, independent contractors, freelancers sourced from online staffing platforms and statement-ofwork (SOW) consultants. But also those non-employed people doing work on behalf of organisations via outsourced contracts (security guards, maintenance, catering, etc.), partners (e.g. people working within the supply chain, partnerships, joint ventures, etc.), formal volunteers and informal volunteers, franchisees, affiliates and associates, and increasingly even nonhuman options can be deployed by way of artificial intelligence, robots, drones and cognitive computing applications. Respondents to our survey suggest these non-employees make up approximately 16% of the workforce on average but higher proportions are not unusual.

While you may not want to entertain the notion of motivating a robot beyond giving it a good polish, why would an organisation not want to incentivise these other categories of workers to do their very best — especially as they represent a sizeable proportion of the workforce? Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs should not be a luxury afforded to the employed workforce only.

One potential issue with engaging and motivating non-employees, and perhaps one that makes organisations reluctant to embrace it with any real enthusiasm, is misclassification risk. Independent contractors are advised to avoid any activities that might suggest they are “part and parcel” of their client’s business. But legislators are mostly concerned with who exerts control in getting the work done. It does not necessarily mean pay structures, bonuses and incentive programmes couldn’t be tailored for the non-employed workforce. Nor that internal communication shouldn’t address the whole workforce, nor that non-employees have to be necessarily excluded from social events such as the Christmas party.

While it certainly pays to be wary and to adopt appropriate policies, a lack of investment in motivation and engagement for any part of the workforce is a missed opportunity for business leaders and a failure for those responsible for brand perception and company reputation.

Many believe non-employed workers will grow as a proportion of the workforce. If so, organisations seem ill-prepared to manage these workers, let alone maximise their full potential. The good news is there is a clear opportunity here for forward-thinking organisations to gain a competitive edge in the war for talent and a market gap for the suppliers of the many variants of nonemployed workers to exploit.