Staffing Industry Analysts’ first UK Engineering Report — released earlier this year and available to European or global corporate members — underscores the importance of engineering to the workforce solutions ecosystem, employment and to the overall economy in the UK. SIA estimates the UK engineering staffing market accounts for just under a third of the total UK professional staffing market.

There are several positive signs for the engineering staffing market among the data in this report. Between 2014 and 2015, the number of engineering enterprises registered for VAT and/or PAYE grew by 6.9% in the UK to 651,080 — the highest growth in more than six years. Furthermore, all home nations and regions, apart from Northern Ireland, saw growth in the number of engineering enterprises in the same period. Scotland experienced the highest proportional increase of any nation with a 25.4% increase, while London saw the highest growth of any region, with the number of registered companies increasing by 10.3% between 2014 and 2015.

There was an approximate 50% increase in the number of UK engineering bachelor’s degrees awarded between 2005 and 2015, with 9% more engineering and technology first degrees obtained in 2015 than the year prior. Also in 2015, England enjoyed its highest number of engineering-related apprenticeship starts in 10 years — and 51% of 11- to 16-year-olds said they “would consider a career in engineering”, up from 40% four years prior.

The report outlines the underlying trend toward the “hourglass economy”: an increasing demand for highly skilled jobs which leverage a strong “STEM” (science, technology, engineering and maths) skills set, and fast growth of knowledge-based services, along with an increase in some lower-skilled and lowerpaying jobs. This trend is taking place alongside a decline in job roles which traditionally make up the middle range of jobs in the skills hierarchy.

The future of engineering — and, more specifically, engineering staffing in the UK — is not without challenges, however. Although the implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU are yet to play out, it seems likely that this will affect both sides of the supply/demand equation. In terms of supply, any tightening of immigration policy or reduction to the perceived attractiveness of studying and working in the UK, or eligibility to do so, are likely to have a detrimental impact on the supply of these key skills.

There continue to be real concerns regarding the industry’s ability to attract young people into engineering, and to retain, motivate and improve the skills of those already in engineering. Despite the increases in the number of graduates in the past five years, the supply of engineering graduates continues to fall well short of demand. We conclude from the report there is a shortfall of at least 20,000 graduates annually. The UK is highly dependent on attracting and retaining international talent from the EU and beyond to help meet this shortfall — a vital part of post-Brexit policy development.

The gender gap. Efforts to attract girls and women into engineering are falling short. Women continue to be sorely underrepresented in the field of engineering, especially when compared to all sectors and occupations in 2015, where women comprised around 46% of total workforce. Boys today are 3.5 times more likely to study A-level physics (in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) than girls; and five times more likely to gain an engineering and technology degree.

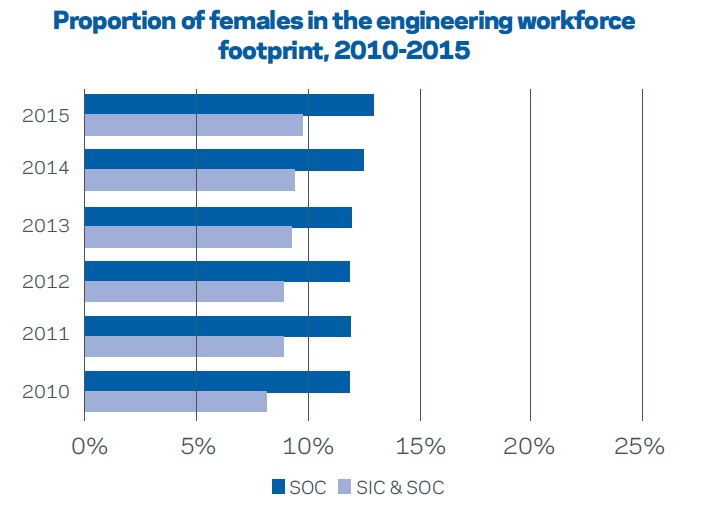

According to data from the Office for National Statistics, women only accounted for one in eight workers: 13% according to SOC footprint (i.e., engineering occupations that are in non-engineering companies). Women comprised an even smaller proportion (just under 10%) of the ”core” (SIC x SOC) engineering workforce (engineering jobs in engineering companies). The general trend since 2010 has been a slight increase in the proportion of women in engineering, which has been more significant amongst the core workforce (SIC x SOC) than in solely SOC engineering occupations.

Given that the demand for engineers outstrips supply, more needs to be done to promote the role and contribution of engineering and technology to the UK and to improve the UK supply of engineers, and of engineering and technology skills. It is incumbent on the government to work with engineering businesses and the education system to develop an industrial strategy that reinforces and sustains engineering’s contributions to the UK, and that recognises and helps to address the STEM skills gap. The strategy should look to increase diversity in engineering through the entire education system and into and throughout employment. This plan should not overlook the talent already in the workforce; it should increase the skills, and improve the retention of existing engineering employees and attract employees from other sectors.

These challenges can be overcome if all those with an interest in UK engineering commit to greater collaboration and partnership. As Britain prepares for a new future post-Brexit, it is crucial that solutions to these issues be found. This would enable engineering to play an ever more vital role in the UK staffing market and the wider UK economy.